Grief Explained: How our brains process loss

- Dnyanada

- September 20, 2024

I vividly recall the day my grandmother passed away. I was anxious about an upcoming exam, and as I hurried to leave for university, I visited her room, kissed her cheek, sought her blessing, and left, oblivious to what was about to happen. During the exam, a call came. ‘Ajji is no more‘ my father said. At first, I couldn’t comprehend the news, experiencing a brief, blissful numbness before a flood of emotions set in. Racing home, I found her covered in a white sheet. The realization hit hard—she was gone.

That moment introduced me to grief in its rawest form – the loud numbness, the confusion, and the pain. Gazing at her lifeless form filled me with an eerie sensation, and the unsettling thought arose: “She was here just 15 minutes ago. Where did she go?”

As I watched her body being placed on a pile of wood for cremation, my mind had already detached, referring to her as “the body.” In just a few hours, all that remained of my grandmother was a pot of ashes.

What is grieving?

Grieving is the emotional process that follows the loss of someone or something we are deeply attached to. While it is often associated with stages like denial, anger, and acceptance, grief is more than just emotions. It is a form of learning—an ongoing process of adjusting to a new reality where the loved one no longer exists.

The non-linear depiction of Kübler-Ross’s model of grief

An illustration depicting how one non-linearly goes through the 5 emotional stages of grief. Source: Pinterest

How grieving changes our brain

Our brain builds a neural map of our relationships based on daily interactions and routines. It helps us predict where, when, and how we’ll interact with our loved ones. For instance, when your partner leaves for work, your brain “knows” they’ll return in the evening, perhaps tired or complaining about the weather. These predictions help us build relationships using very little brain computing power.

But when a loved one passes away, especially suddenly, our brain must redraw this map.

Grieving is a process of learning

Our brains must reconcile two conflicting data points:

The new information that our loved one is gone

The deeply ingrained information that our loved one is everlasting

The latter manifests as a desire to reunite with our loved one. Interestingly, many individuals in the early stages of grief report sensing the presence of their departed loved one—whether by glimpsing their silhouette in the dark or hearing their voice in fleeting moments. Others experience interacting with them in their dreams.

Each encounter with the harsh truth of the loss can be emotionally painful. For example, visiting my grandmother’s empty Pooja room was a painful reminder of her loss and helped me to re-wire my neural map.

What happens when we don’t grieve?

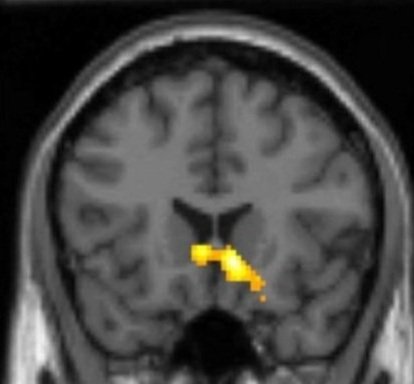

When we don’t allow ourselves to grieve, the emotional pain of the loss can linger, often resurfacing later in life. This is known as “complicated grief.” Research shows that while both non-complicated and complicated grief involve increased brain activity in pain-related areas, those with complicated grief also exhibit heightened activity in regions associated with “anticipation”. This brain activity for anticipation positively correlated with reported desire to meet the lost one, suggesting a difficulty in accepting the loss.

Common types of complicated grief include:

Grief denial: When individuals suppress their emotions and carry on as if the loss never happened. For example, someone might return to work the day after losing a loved one, refusing to acknowledge the loss.

Chronic grief: Prolonged grief is characterized by persistent sadness, anger, or anxiety that doesn’t ease over time. For example, a parent who has lost a child may remain engulfed in sadness for years.

Complicated grief linked to heightened desire for reunion, brain scans show.

Source: O’Connor MF et al, 2008

Traumatic grief: A sudden or shocking loss can leave individuals overwhelmed, requiring trauma-specific therapy. For instance, witnessing a fatal accident involving a close friend can leave someone stuck, reliving the traumatic event in flashbacks, unable to grieve properly.

Delayed grief: Emotions are postponed due to environmental pressures. For example, a soldier might have to suppress grieving over a fallen comrade because of an ongoing war

System-restricted grief: Family dynamics or societal expectations often dictate how someone should grieve, leaving one person to manage others’ grief without addressing their own. For instance, after the death of a father, the eldest son feels pressured to manage the household and suppress his own feelings to support his mother.

Conclusion

Grief is a deeply personal journey, and there’s no set timeline or “right” way to experience it. The process of relearning a world without a loved one can be slow and painful, often taking longer than we anticipate. There is no shame in needing time or in wanting support along the way. Each individual grieves differently, and it’s important to honor your own pace—whether through rituals, seeking support, or simply allowing yourself to fully feel the emotions that accompany loss.

Many people feel pressure to “move on” or “stay strong,” but grief is not something you can rush or suppress. It’s okay to ask for help, whether from friends, family, or mental health professionals. Surrounding yourself with a support system can make an immense difference.

We hope, in time, you find the light at the end of the tunnel and the peace that comes with it.

Liked what you read?

Sign up and get the latest blog posts delivered straight to your inbox.

Related Arcticles

Domestic Violence Among Indian Families and its Impact on the Brain

In Indian families, domestic violence often hides behind cultural norms. This blog reveals shocking statistics and its impact on the brain.

Craving Connection: A Scientific Look at Why We Feel Lonely

Dive into the neuroscience of loneliness and discover why our brains crave real connection.

Figuring out your identity after the big fat indian wedding

Explore the identity struggles women face after marriage, from navigating family ties to redefining your place in the world.